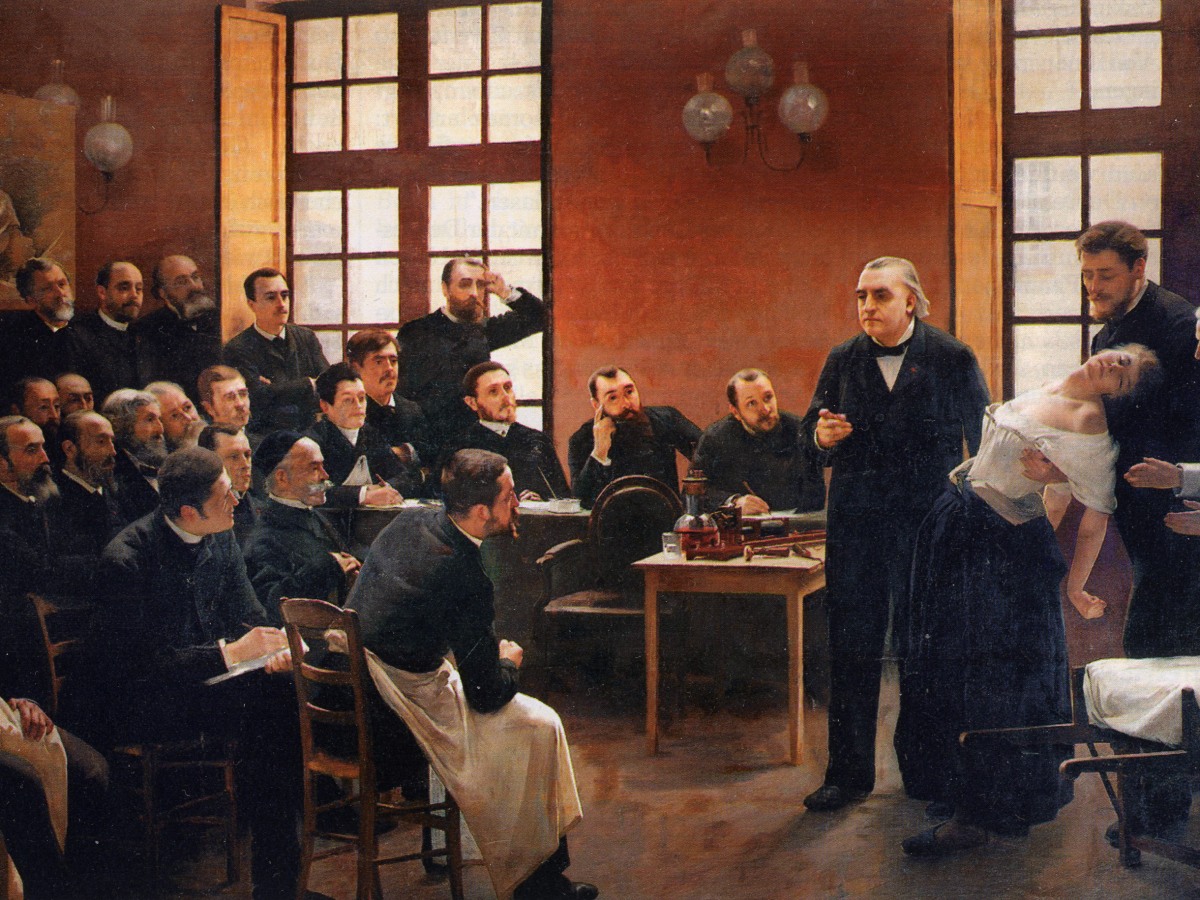

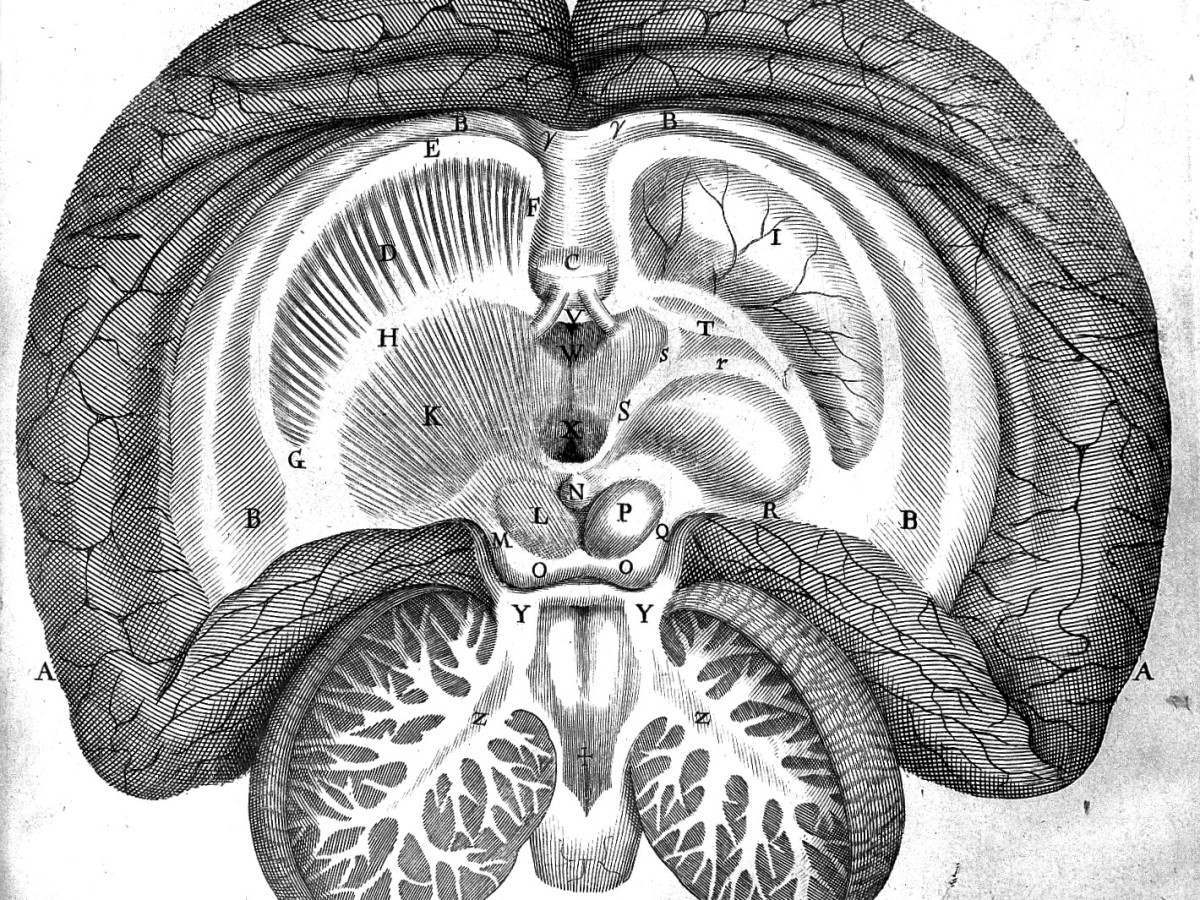

For many patients we can discover – or discount – physical causes of neurological problems ‘in real time’ with a range of imaging and other measurement techniques. Neuroimaging techniques are mainly children of the 20th century, and their development is ongoing in the 21st, but their roots stretch back through the 19th century. For example, photography and its ability to reproduce an enduring ‘objective’ image had a major impact when it was introduced and that extends to the study of the brain.

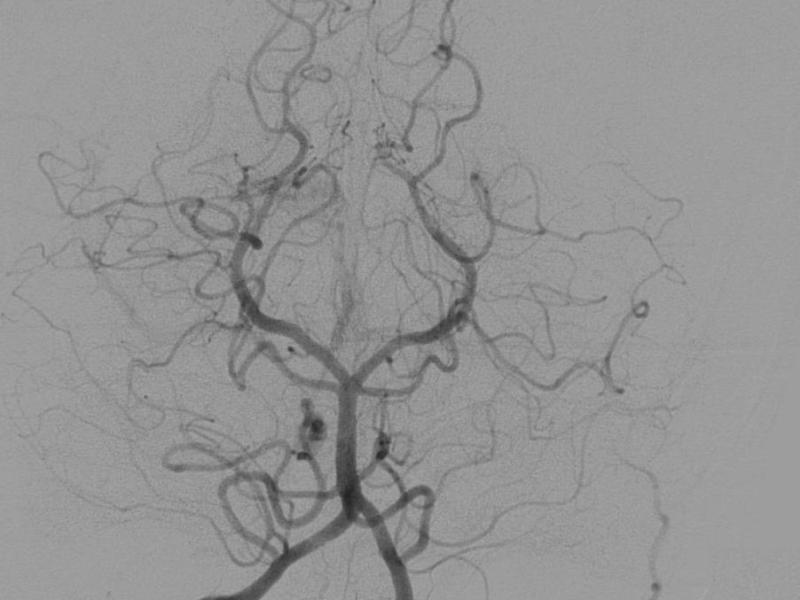

But a ‘normal’ camera operating in the visible (to us) spectrum of light can only see what is directly in front of it. Exposing a brain so you can see what is going on inside it carries risk. This means that – outside of an autopsy – doing so is only ever going to be justified in a small number of people. A way to investigate the structure and operation of the brain in a non-invasive way was needed.

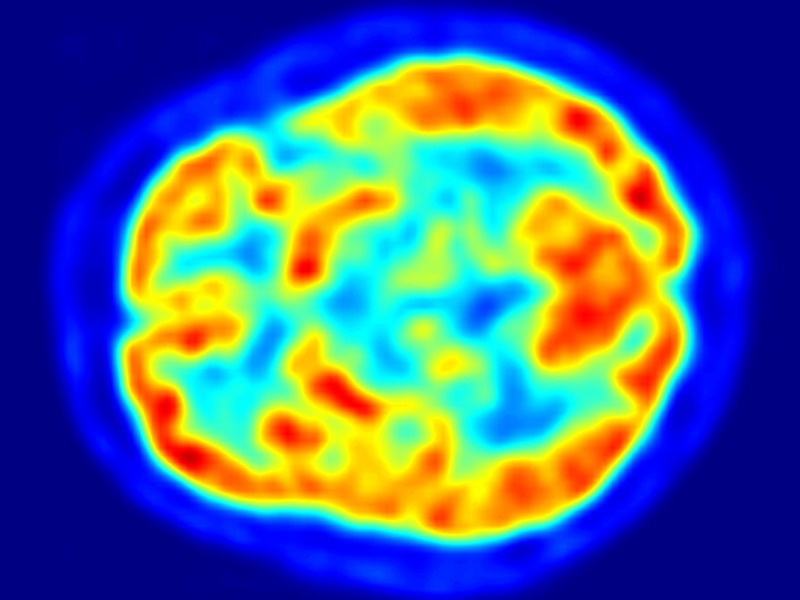

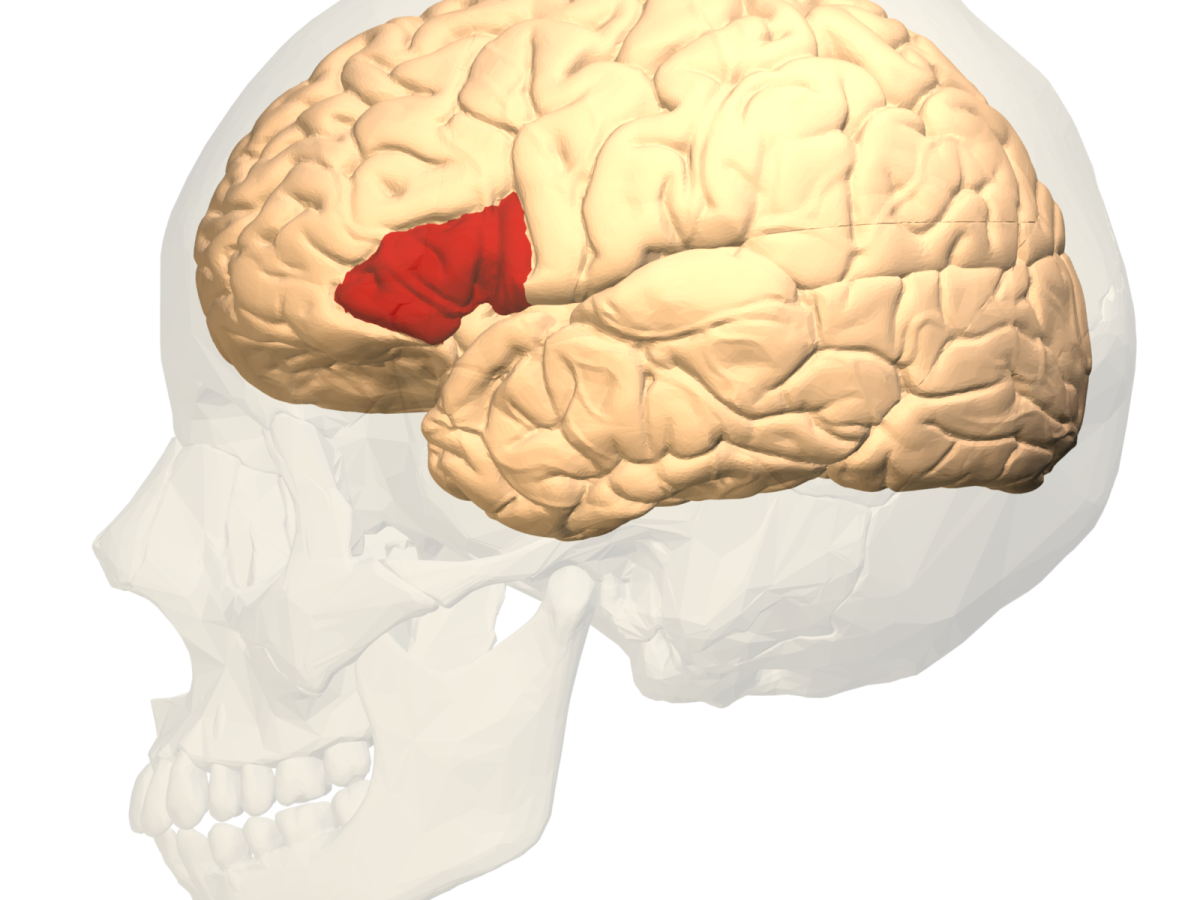

Like MRI in general, functional MRI depends on differences in magnetic properties that are linked to physiology. The functional bit refers to the fact that MRI can be sensitive to something other than brain structure, like the types of scans covered in the posts linked above. fMRI is sensitive to brain activity. By ‘activity’ in this case we mean something different than the electrical or magnetic fields produced by neurons as measured, via fewer intermediary steps, by EEG or MEG. Activity in fMRI is not directly about neural activity, but about blood.

Continue reading “I see what you did there…a (very) brief history of imaging the brain: blood, BOLD and fMRI”