I’m really nothing more than a photographer. I record what I see.

Jean-Marie Charcot, 7 February 1888

Hi Francesco, tell us a bit about yourself

Hi Ben, thank you for inviting me to your blog! I was born and raised in Udine, a small town in the north-eastern part of Italy, but I currently live in Modena and work in Bologna, at the IRCCS Istituto delle Scienze Neurologiche (Institute of Neurological Sciences). I started off my medical career as a full-time clinician, working my way up through many locums around Italy. It was a hard training but it gave me a chance to strengthen my competences in neurology by applying them to many other medical fields, from rehabilitation to ER, and to experience relationships with patients in diverse settings. I have been interested in epidemiology since my graduation in medical school, and about twenty years ago I made a big change in my career, devoting myself to epidemiology and the methodology of medical research while narrowing the time of spent on clinical practice (though I still do one day a week, since I think that even in a research setting it is important to see patients and listen to them).

Want some local neuro-history from Bologna?

My other great interest is in photography, that I have pursued since I was a teenager. I started taking pictures and building my own darkroom in the 1970’s, when photography was entirely analogue. I am self-taught, although I read many books and have attended workshops on various technical and historical topics about photography. My artistic production is often influenced by the relationships between photography and science. I am particularly fascinated by taxonomy, the effort of finding a name for each manifestation of nature, often based on its shape, which photography allows the representation of so accurately.

My interest in Cochrane came in the 1990’s when I was lucky enough to meet and work with Alessandro Liberati. He was an extraordinary person. His energy and enthusiasm were contagious and ten years after he passed I still feel every day his strong legacy. Currently I am co-ordinating editor of the Cochrane Review Group on Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the CNS.

You work in neurology and have a passion for photography, as well an interest in the history of both. Is there overlap between these areas of interest?

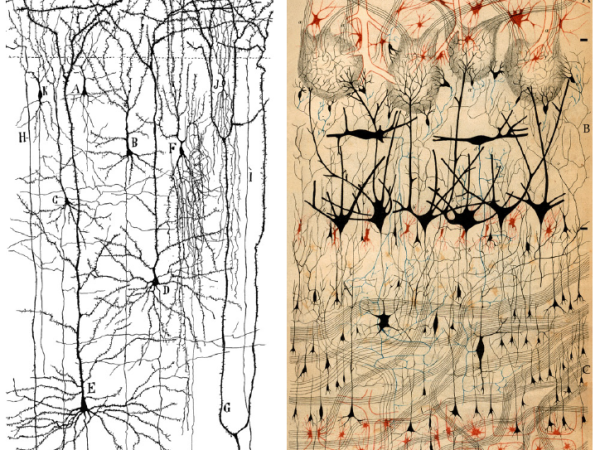

Definitely. In the second half of the 19th century photography, among other effects, opened up unprecedented documentary possibilities in the scientific world. In fact, photography was announced as a new invention on January 6, 1839, at the French Academy of Sciences. For the first time it was possible to capture a detailed, reproducible image. It made it possible to compare images of the same individual over time or between individuals with similar features. Also, because it was carried out by a machine and produced a direct trace on a physical medium it was considered to be much more ‘objective’ and reliable than, for example, hand-drawn sketches.

Can you tell us about some of the ways photography influenced science and medicine?

The first to systematically use photography in the medical field was a neurologist, Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne (1806-1875). Duchenne published ‘Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine’, including a series of photographs (taken by Adrien Tournachon, better known as the brother of Nadar, 19th Century photography pioneer) that document Duchenne’s studies of the mimic or facial muscles which are responsible for making expressions. They feature a patient suffering from a peculiar insensitivity of the face, allowing Duchenne to apply metal electrodes to the patient’s skin and electrically stimulate specific muscles. Duchenne’s work aroused great interest among scientists of the time, including Charles Darwin. In 1872 Darwin published ‘The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals‘ in which the expressions of humans and primates are analysed and compared, in the context of his evolutionary theories. It included photographs by Duchenne and others.

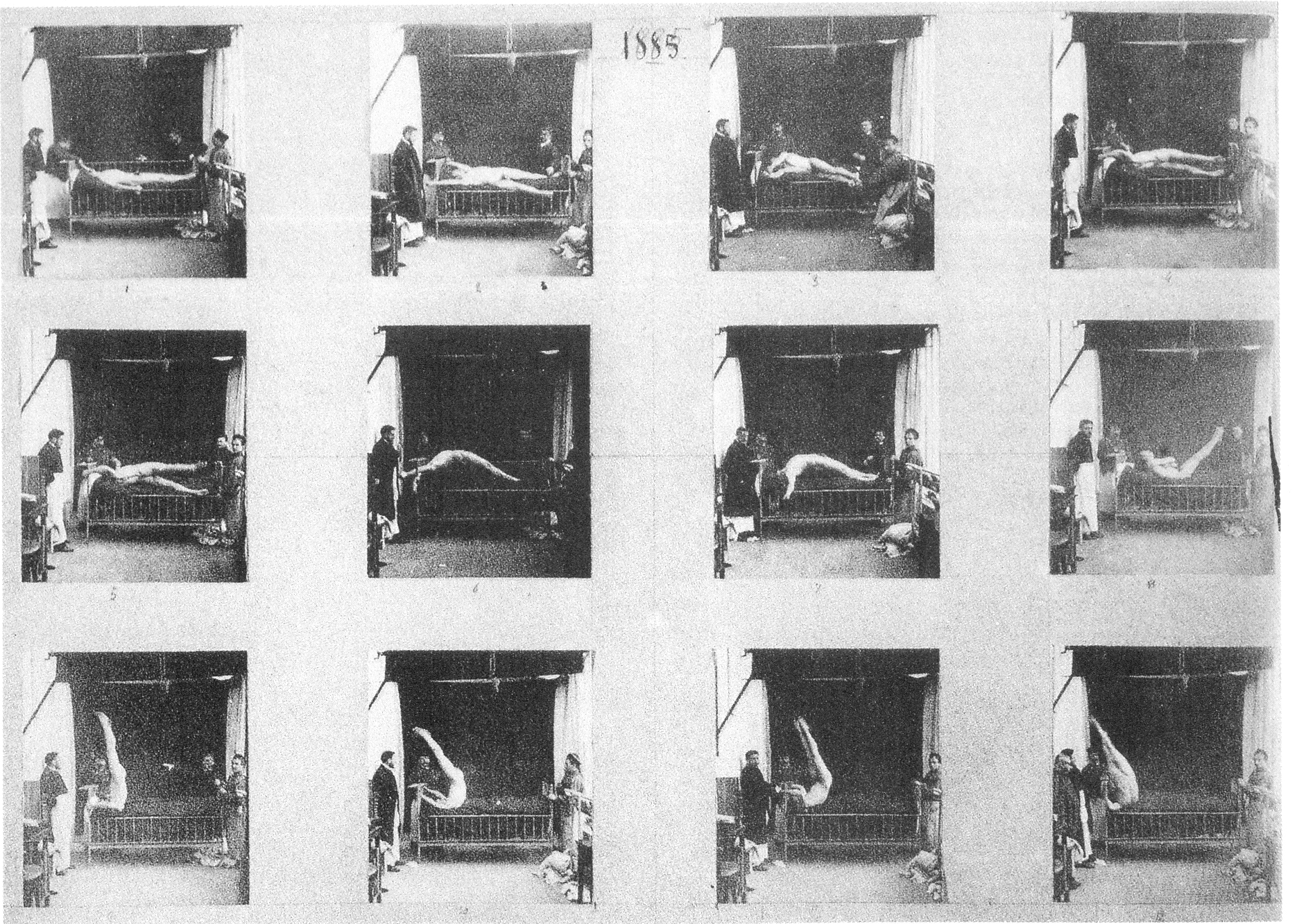

Another good example of how photography contributed to scientific knowledge is the monumental work of the American photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1840-1904), a pioneer of chronophotography. He produced over 100,000 photographs of humans and animals in motion, with the aim of observing and analysing the aspects of human and animal movement that could not be captured with the naked eye:

From Wikimedia

In a previous post I noted that if the birth of neurology could be associated with a particular place and person, it would be Hôpital universitaire la Pitié-Salpêtrière at Paris, and Jean Martin Charcot. (1825-1893) who worked and taught there for 33 years. The same names are important for the intersection of photography and neurology, correct?

Absolutely. In 1866, Charcot started a free course on nervous diseases which became a huge success in just a few years, attracting students (including a young Sigmund Freud), doctors and scientists, but also leading figures from the world of culture and art, partly thanks to the ‘spectacular’-ising of clinical cases. Charcot, with collaborators like Alfred Vulpian and Pierre Marie, described multiple sclerosis (differentiating it from Parkinson’s disease) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The ‘Salpêtrière School’ worked widely on diseases of the spinal cord, progressive muscular atrophy, syringomyelia, neurological manifestations of syphilis and alcoholism. Clinical studies lead to a revision of the classification of several neurological fields, such as paralysis, tremors, chorea, vertigo and epilepsy. Charcot and the London physician William Gowers (1845-1915) were the first to attempt a differentiation between hysteria and epilepsy and this interest is probably to be found in the desire to separate diseases of the ‘body’ from those of the ‘mind’, which was the origin of neurology as an autonomous speciality.

Charcot saw photography as a valuable scientific tool and promoted its widespread use to document in detail the clinical manifestations of neurological diseases. The importance of photography in neurological research at La Salpêtrière grew to such an extent that the hospital set up a photographic studio and laboratory, directed by a professional – Albert Londe – who, thanks to his work at La Salpêtrière, was to become one of the most important scientific photographers of his time.

.

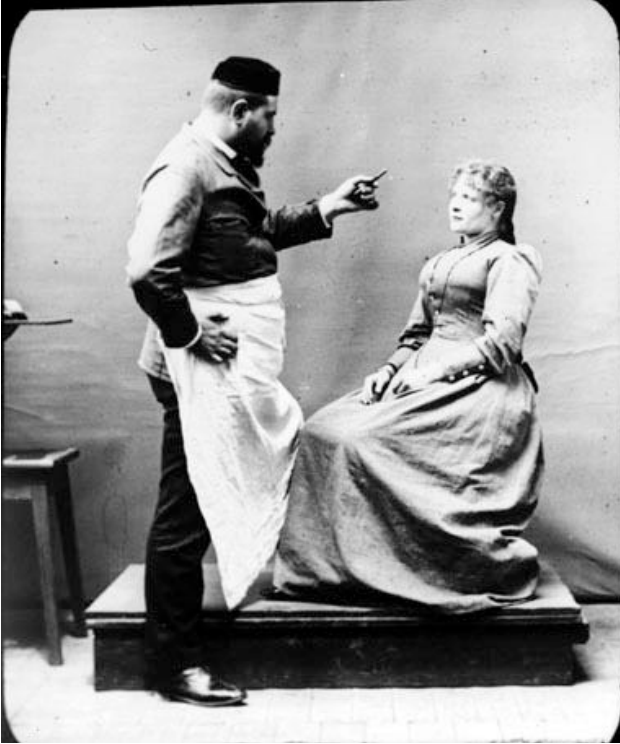

Hypnosis formed another part of the method for JMS, correct?

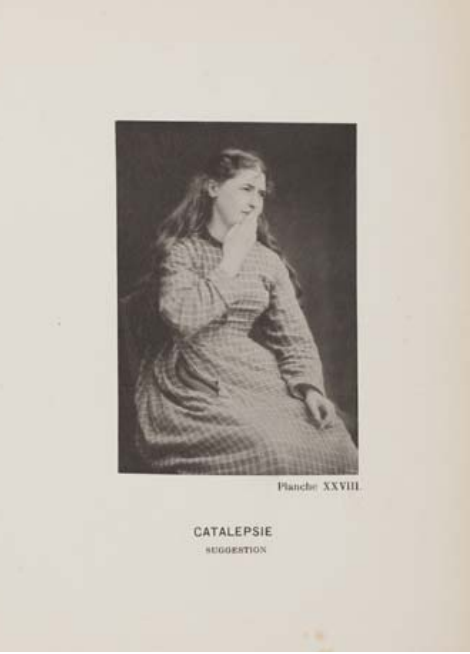

Hypnosis was the instrument that allowed him to ‘induce’ scientific tests in his patients, reproducing them at will in what JMC considered an experimental setting. This instrumentalization of hypnosis can be seen in two respects: on the one hand, it made it possible to ‘visualise’ – at will – phenomena accompanying hysteria (paralysis, anaesthesia, selective colour blindness…, what we now call conversion symptoms) making them document-able and reproducible. At the same time, hypnosis made it possible, in a more pragmatic sense, to immobilise the subject in particular postures (considered ‘pathognomonic’ of the disease) for the time necessary to photograph them. One of the main limitations of photography at the time was the slow pace of execution and the need of very long exposures (due to the low sensitivity of early photographic emulsions), which made it difficult to photograph animated subjects. Hypnosis, by creating a state of both fixity and ‘malleability’ (through the possibility of inducing postures and expressions at will) of the subject had in a sense a similar purpose to that of the accessories (platform, headrest, support arms) used by Albert Londe to facilitate the immobility of the patients during the long exposure times necessary to take a photograph.

It is noticeable that in these photographs reflect the sensibilities of a different time, and the people in the photographs don’t seem to be always treated in a way we would expect by the standards of today. Is the case for the work of JMC as well?

The most obvious element that unites all the photographs in the hysteria series is first and foremost the exclusive presence of female subjects as ‘cases’ being studied through hypnosis. As an example, one image shows a young woman captured in the act of blowing a kiss. The photograph is structured to record both her expression and her posture. The woman has long loose hair, a dreamy look and a sweet smile. From the description in the text we know that the image was taken while the woman was in a state of catalepsy: after being hypnotised, her eyelids were forced open and her limbs were positioned in the attitude of a kisser and, according to JMC’s theory, her expression changed accordingly. This ultimately testifies to an instrumentalisation of the female figure. The woman presented in this way, suffering from the “ovarian hysteria” – a gendered disease – is dominated by the “doctor-hypnotist” who decides at will to make her go from one stage of hypnosis to another, and to make her assume postures to which she conforms with “congruent” expressions (fear, tenderness, etc.) following cultural stereotypes (the frightened woman, the temptress woman, etc.). Here we have young women with a low level of education, belonging to the most disadvantaged classes in society at the time, influenced by the person who, compared to them, represented the opposite end of the social scale: Professor Charcot, and more generally the Doctors of La Salpêtrière. Photography, perceived as infallible in its truthfulness, thus also served as an effective tool in reinforcing the social hierarchies of the time, visually reproducing the paradigms of “being a woman” and at the same time the power relationship between doctor and patient.

Was the association of photography and ‘objectivity’ justified?

In the absence of anatomo-pathological correlates, the visible symptoms of hysteria (paralysis, pseudo-epileptic seizures, behavioural disorders) were the only material for researchers to study. In the phrase ‘I can see, I can photograph, therefore what I see has existed’, JMC takes two things for granted: the first is that the camera mechanically, passively and therefore objectively records what is in front of it (and it therefore exists), the second is that the appearance of what exists contributes substantially to its explanation. Photographic recording of what was observable externally made it possible to catalogue what was macroscopically visible, giving the world evidence of a condition that eluded all attempts at classification due to the heterogeneity of its manifestations. It was later realised that the origin of this heterogeneity lay in the fact that the term ‘hysteria’ encompassed several conditions, some of them organic (e.g. epileptic syndromes, primary and secondary) and others purely functional (somatoform disorders and conversion symptoms). Photography in the 1870s was seen as the most objective means of representing reality and whose certifying power was sufficient in itself to guarantee scientific validity. Today we know that this is not the case: the reality represented by photography is the result of a choice and an interpretation by the operator that threaten its objectivity no less than with other methods of visual representation seen as less ‘objective’.

Your Brain…in Images: Seeing is believing. Maybe.

In the context of modern science ‘seeing is believing’ can be a tricky concept: the observer is always several technological and methodological steps removed. In the context of brain science, it’s hard to get direct evidence without breaking the very thing that piqued your interest in the first place.

How does this compare to modern neurology?

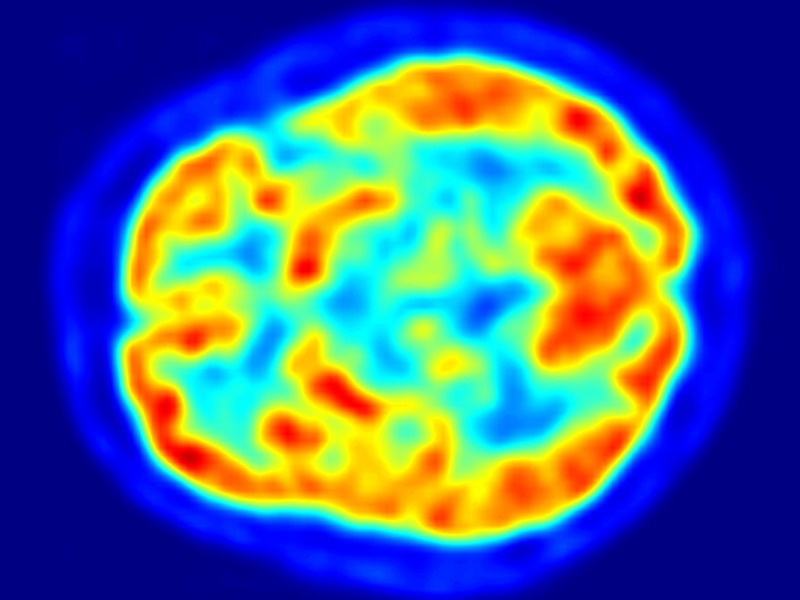

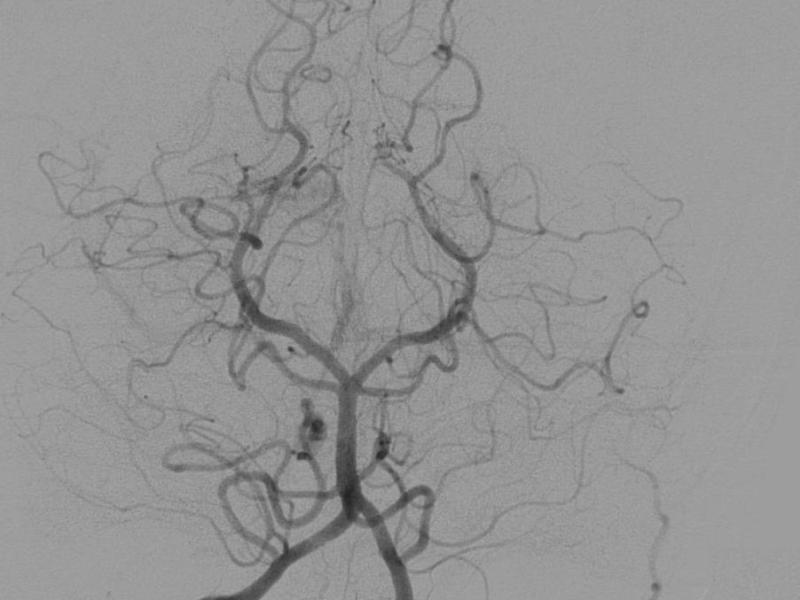

The evolution of sonographic and tomographic imaging techniques (ultrasound, computed tomography, radiolabelled diagnostics, nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMR), and more recently functional and spectroscopic NMR), essentially represent evolutionary steps from the photography that excited JMC and his collaborators. Today’s “photographs”, unlike those of the past, are digital. Instead of film, there is a sensor that translates light into algorithms, which are then converted back into images. In the language of semiotics, they do not produce an ‘index’ (a trace, imprint) with a direct physical relationship with the referent, but an ‘icon’ that requires a code in order to be placed in relation to the referent. These techniques have increased our chances of seeing something. But there is also a greater possibility of encountering something visible to which we do not know how to give an explanation. So this greater capacity is sometimes not a resource but a problem involving difficult choices for the doctor. This can include the discovery, by chance, of radiological signs with unknown prognostic value. Once we have this information, whose prognostic significance we do not fully understand, what do we do with it? We can share it with the healthy person in front of us, but we must take into account the effects that the suspicion of future difficulties can have. The alternative is not to communicate this information to the person, thus assuming a paternalistic attitude that is open to criticism in that it denies the possibility of shared choices between doctor and patient, depriving the latter of his or her autonomy in making decisions regarding his or her own health.

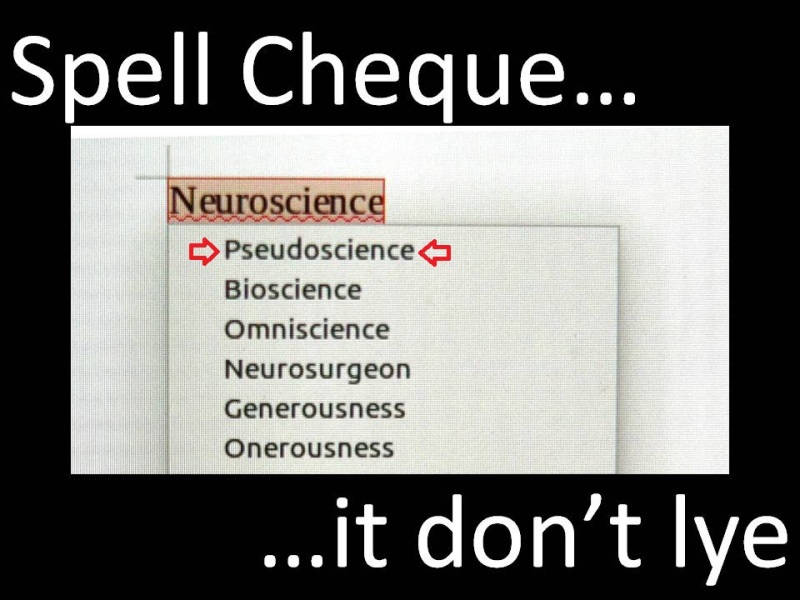

The rudeness of fish and algorithms: Spell check don’t lie

Technology, when it works seamlessly, is fantastic – it just does what it does, and you don’t have to worry about the how. But when it fails that’s when a certain truth is most evident: GIGO. Garbage in, garbage out.

Thanks for your time Francesco.

More interviews can be found here:

Interview with Tiffany Duque, Cochrane US : Global Health, Pandemics (Infodemics!), Brains & Books, Books, Books

Tiffany Duque, Senior Officer at the Cochrane US Network, tells us about her work in global health and with Cochrane, the pandemic and (most importantly!) book recommendations.