“Ignorance killed the cat; curiosity was framed!”

― C.J. Cherryh

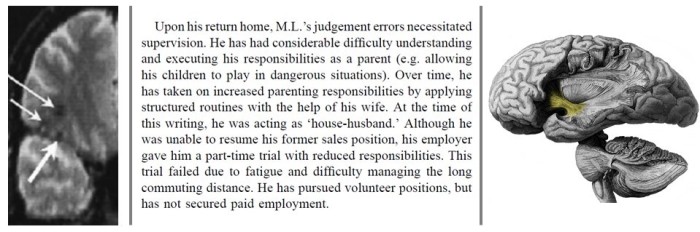

In the real world, retrograde amnesia refers to the forgetting of explicit information (including episodic/autobiographical and semantic/factual) of already information. This can be temporary, or more permanent in severe cases. Patient ML is a well-known case of ‘pure retrograde amnesia’ [1]. After a car accident, they suffered damage to their right ventral frontal cortex and in a white matter tract (or brain road) known as the uncinate fasciculus, which connects the temporal lobe and the frontal lobe. The figure below provides some more detail on this damage and the difficulties faced by Patient ML, directly and indirectly, because of his inability to recall previous experiences and learned facts.

The ‘mindwipe’ trope or the accidental or deliberate erasure of memories is a recurrent theme in films and science fiction and often paints a picture where amnesia can be induced without impacts on wider functioning.

An award-winning novel of conflict and ambition

The inspiration for these thoughts on the representation of memory were prompted by C. J. Cherryh’s Downbelow Station. To be clear, I think this is an excellent book. Tropes can serve as shortcuts that the audience understands: tropes aren’t always bad, as long as they don’t break the (magnetic) suspension of disbelief. But it’s always worth interrogating them and, in any case, it gives me a chance to talk about my twin passions of neuroscience and SPACE MAGIC!?! science fiction.

To get a sense of its themes, check out this out:

“We go over the next hill, live a few hundred years, change our languages to accommodate things we never saw before—and before we know it, our cousins think we have an accent. Or we think they have a strange attitude. And we don’t really understand our cousins any longer.”

― C.J. Cherryh, Downbelow Station

The scope is operatic, the setting and world-building are science-fictional, with the emphasis on new human situations rather than on technology or speculative physics. A tight focus and the human scale make this book quite special. The larger context is explored at the level of the people in it, and we care insomuch as we care about them. No hero, such as they exist, is unconflicted. No antagonist, such as they are, is totally unsympathetic. The book has been recognized by multiple awards, both at the time of publication (1981) and in All Time Best listings since, and by the way cool fact of having an asteroid named for its author and songs sung about its characters.

The need for Adjustment

In the book an interesting subplot deals with a prisoner of war called Josh Talley. He’s previously been subject to an illegal use of the setting’s native mindwipe technology referred to as Adjustment, in an attempt to extract strategic information, and has suffered through a voyage marked by sexual exploitation. Another major theme is an examination of how the needs of the individual can be subsumed by those of the group. Downbelow Station and environs is portrayed as more-or-less free society maintained in the face of resource constraints in the unforgiving physical environment of outer space and the buffeting of a dangerous political environment. Despite wanting to remain neutral, the station is in danger of becoming another front in a multi-faceted conflict involving both cold and hot war. A new strain, represented in the person of Josh Talley, is the arrival of refugees. The disruption on the station leads to friction, and the question of how to deal with it.

In Downbelow Station, the goal of Adjustment seems to be a more or less pure retrograde amnesia, though the book doesn’t go into how this specificity is achieved or how they avoid the creation of problems in addition to ‘just’ memory loss. The character has feelings and ‘senses’ regarding names and places even if he doesn’t explicitly recall them, and conditioned responses such as those that might be acquired by military training appear that show through at certain moments. This dissociation between implicit and explicit knowledge is something that this depiction, and the trope more widely, often gets more or less right.

Permanent Present Tense

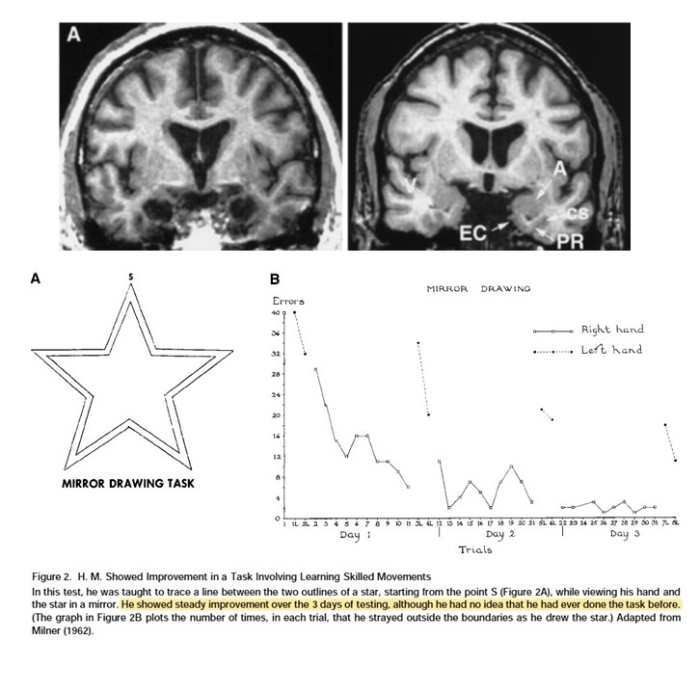

Patient H.M. (or Henry Molaison as we now know), has contributed enormously to the understanding of different aspects of memory through his willingness to be the subject of dozens of studies over the years [2]. HM underwent surgery in 1953 to control his epileptic seizures, including the removal of large parts of his temporal lobes on both sides of his brain. The surgery was successful in the sense of resulting in a large reduction in seizures, but it was found that HM was now unable to form new memories. This is anterograde amnesia, in contrast to the retrograde amnesia we’ve discussed so far. While anterograde and retrograde amnesias result in the inability to recall explicit information (Facts, memories, details) they often leave other types of learning more or less intact. Implicit memory refers to information acquired and ‘recalled’ unconsciously, often relating to motor or procedural learning. A well-known study involved HM learning a new skill (see the figure below), in this case the reproducing a star shape without straying outside the outlines while viewing the task only in a mirror. Over several days, HM showed improvement in this task, despite having no memory that he’d ever done it before.

Intense Internal Voice

In science fiction brain-altering technology in the context of the justice system is commonplace, a trend that’s likely informed by the (deservedly) dodgy associations acquired by psychosurgery given some of its 20th century history. What makes it stand out in Downbelow Station is the fact that it’s presented as neither an unalloyed and unexamined good that is not commented upon, nor a simplistic evil. It’s highlighted early that the available physical prison cells are temporary, few in number, and in contrast adjustment is seen as more akin to treatment than anything else, reserved for violent cases and for those that opt into the procedure. One protagonist, while not doubting the wider system, agonises that Talley is willing to go through with it the procedure as a means of escape, of suicide. But there’s a process (legalistic and medical) to assure the procedure is used appropriately, and Josh Talley satisfies these constraints. Recognising that he’ll never go home and faced with indefinite imprisonment in a setting that apparently has no habitual need of long-term detention, Josh Talley chooses to forget in return for his freedom, volunteering for Adjustment.

In lesser hands, the story of a radical surgical alteration carried out on the body of a refugee could go very wrong. Down below station doesn’t flinch from these issues, in my opinion. It’s important to note that we only know the characters’ thoughts on these things, because of a narrative style the author refers to as “very tight limited third person“, “intense third person”, and the “intense internal” voice, resulting in a sort of ‘floating narrator” but one that is restricted to describing the thoughts and feelings of the character and what they notice and react to in their daily life. The author leaves us to make our own decisions about the ethical issues raised in the story, including several perspectives but without any final authorial fiat on who (if anyone) the goodies and the baddies are. Indeed, later instalments in the series are told from the perspective of the other belligerents in the brewing conflict. This ambiguity is compelling, and unfortunately also has parallels in the real world where the people who make the decisions are not those that bear the costs.

Never (again)

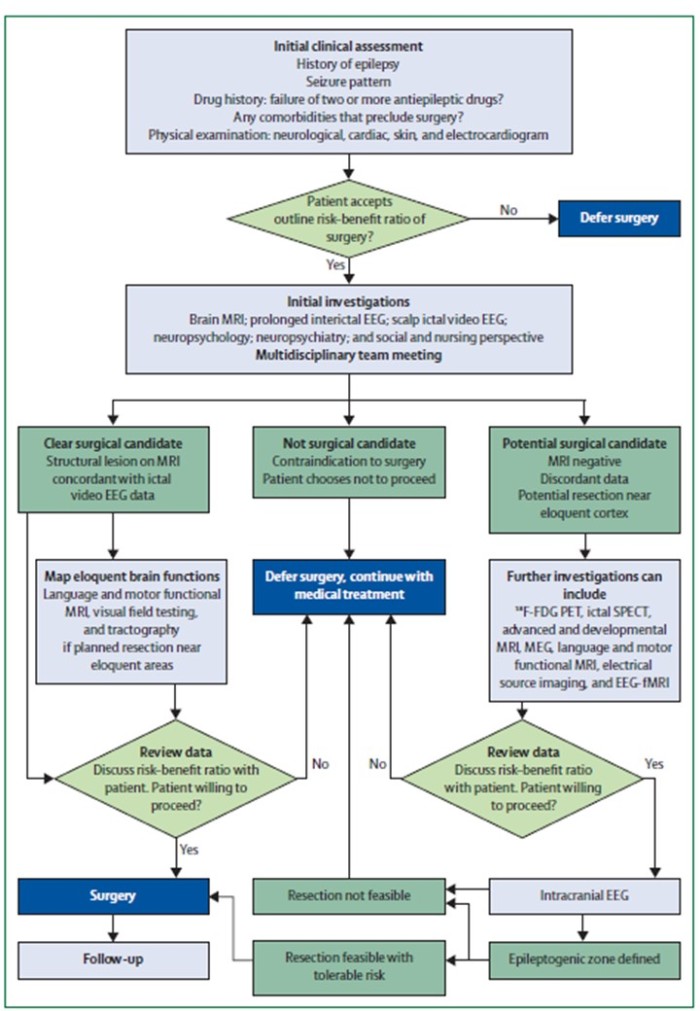

Back in the real world, brain surgery as a treatment for epilepsy continues to this day as an option for patients whose seizures are insufficiently controlled by medications, or who don’t tolerate other treatments. A lot of work goes into assessing each case as a surgical candidate to ensure the probability of success is sufficient to warrant the risks that come along with any invasive procedure, and specifically to try to avoid or minimise any cognitive problems due to functional tissue being removed. The figure below gives an idea of the flow of investigation that might go into answering this in a given patient.

Over the past few years more detail (Including a biography Permanent Present Tense) has come out about HM’s life and the factors that contributed to his condition [6], including extremely problematic details relating to how his surgery was conducted. Surgery is normally an option for focal epilepsies, where the seizure is thought to start from a more or less specific part of the brain and is not normally used in cases of generalized epilepsies with simultaneous onset in multiple regions. HM likely had generalized seizures [6], so why was he operated on? Furthermore, it’s thought likely that the surgeons operating on him were aware that HM’s epilepsy was a generalized form. They operated anyway, apparently on the basis of a pet theory – possibly informed by a history of involvement with psychosurgery – that seizures occur once a threshold was reached and removing tissue, any tissue, would raise that threshold. It’s worth reiterating that this wouldn’t happen in a properly functioning neurology department today. Regardless, it’s clear that HM’s case not only embodies one of the most famous single neurology cases that has seeped into the collective consciousness and helped elucidate the workings of memory, but also a stark reminder of the costs of lapses in professional oversight especially in medicalised contexts.

I think it’s worth repeating the words of the author’s,

“H.M.’s case will remain as a historical monument in the quest for knowledge about human memory and human epilepsy. The past is past, but we should never see another case H.M.” [6]

Biographical note about the book

The author’s pen name was constructed from her given name – Carolyn Janice Cherry – to obscure the fact of her apparently unsellable womanhood with the initials ‘C.J.’ and by the adding of a silent ‘h’ to her surname to science-fictionalize it, on the theory that ‘Cherry’ sounds too much like a writer of romance novels (…clearly the wrong sub-genre of The Genre With No Name). The extent to which the factors contributing to those decisions continue to be relevant or important (i.e. the more things change, the more they stay the same), I’ll leave as an exercise for the reader.

References

[1] B Levine, S E Black, R Cabeza, M Sinden, A R Mcintosh, J P Toth, E Tulving, D T Stuss, Episodic memory and the self in a case of isolated retrograde amnesia., Brain, Volume 121, Issue 10, Oct 1998, Pages 1951–1973, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/121.10.1951

[2] Corkin, S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.?. Nat Rev Neurosci 3, 153–160 (2002) doi:10.1038/nrn726

[3] Suzanne Corkin, David G. Amaral, R. Gilberto González, Keith A. Johnson, Bradley T. Hyman (1997) H. M.’s Medial Temporal Lobe Lesion: Findings from Magnetic Resonance Imaging Journal of Neuroscience, 17 (10) 3964-3979; DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03964.1997

[4] Milner B1, Squire LR, Kandel ER. Cognitive neuroscience and the study of memory. Neuron. 1998 Mar;20(3):445-68.

[5] Duncan, J.S., Winston, G.P., Koepp, M.J., Ourselin, S., 2016. Brain imaging in the assessment for epilepsy surgery. Lancet Neurol. 15, 420–433. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00383-X

[6] Mauguière F, & Corkin S (2015). H.M. never again! An analysis of H.M.’s epilepsy and treatment. Revue neurologique PMID: 25726355

2 thoughts on “Your Brain on…Books: Misadventures in neuroethics with C.J. Cherryh’s “Downbelow Station”, Patients M.L. and H.M, and the mindwipe trope”