You’re probably familiar with the basic story of how vision is supposed to work: photons of light are reflected from objects and interact with specialised photoreceptor cells in your retina, that outermost part of your visual system that filters and extracts features of the incoming stimuli.

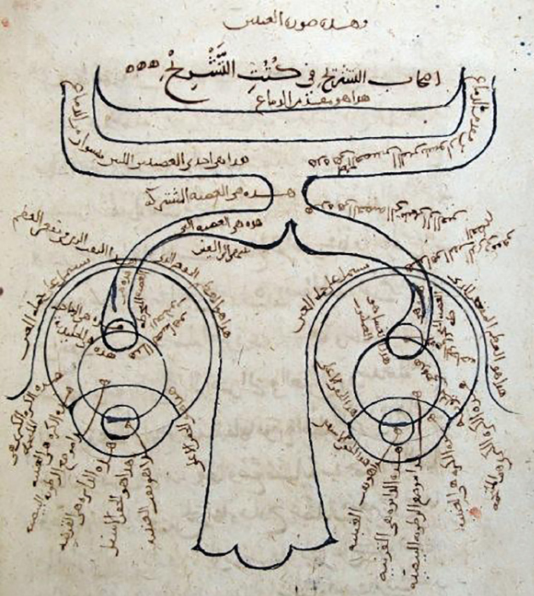

Even if the jargon is modern, the basic idea isn’t new. It’s what’s know as the intromission theory of vision, and it casts your eyes as essentially passive sensors of incoming information and has been proposed in one form another since Democritus, Aristotle, Epicurus and Lucretius [1]. Historically, there was an alternative extramission theory, held by such luminaries as Alcmaeon [1], Plato and Empedocles, for whom there was a kind of fire projected from the eyes which interacted with objects and resulted in ‘seeing’. There were always those that were unhappy with this latter account, for example when you looked up at night, was this fire really racing from your eye to the stars and filling the whole sky? But the downfall of the extramission theory as a credible account of vision is most associated with Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (a.k.a “Alhazen”). Offering not just critiques, he salvaged the useful aspects of the geometrical treatment of the projected ‘rays’ by extra-mission proponents like Euclid and Ptolomy, and rendered them into an essentially modern account: rays reflected from objects and enter the eyes (are not produced by the eyes), and the process of seeing happens in the brain.

But if extramission theories of vision have been discredited among experts and specialists for a long time, folk beliefs about extramission and more generally a special potency associated with the eyes have retained their power and remain prevalent. Take, for example, the widespread belief in the evil eye – the power of a malevolent gaze to cause to misfortune – and the apotropaic magic used to combat it.

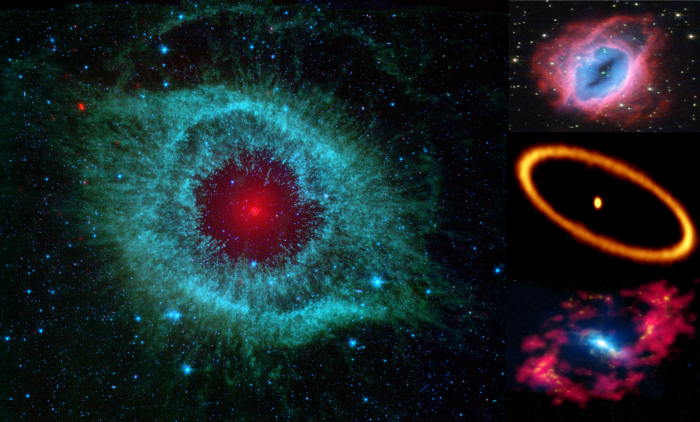

Fiction also makes use of the idea of the evil eye and the deadly gaze: the Eye of Sauron, belonging to the big bad in the Lord of the Rings, is represented as a giant, flaming evil eye. As I discovered while researching this post, this iconic representation is not lost on astronomers given the range of astronomical phenomena named or nicknamed after this very eye (see below). This would seem to reflect the fact the eye is a special stimulus for us: we apparently can’t help but see it everywhere, even in things that themselves are entirely nothing to do with the eye (a kind of pareidolia). It also suggests that astronomers should widen their literary influences (maybe they should keep an eye on the Your Brain on Books tag or follow my Goodreads shelf).

Myths from many cultures include beings whose special potency is mediated by their gaze, if not always their eyes. Medusa, who had the temerity to be raped by Poseidon in one of Athena’s temples and was victim blamed cursed by the goddess so that all who saw her face would turn to stone, is an obvious example. Perseus, who apparently made a habit of torturing mystical women with eye issues, had a run in with three old women – the Graeae – whose shared single functional eye he held hostage until they gave him information needed to take out Medusa. Odin has many names and but a single eye while Shiva has a third eye and both outcomes are associated with knowledge and special power: the sacrifice required and its attainment, respectively.

So why the fascination with the eye, and specifically the idea of forces and influences directed out from the eyes and influencing things in the world? Psychology raises the possibility it reflects an underlying model we use to understand the attention of other people. That is, even if we have explicitly learnt the correct intromissive model, we have an implicit model that leads to the prevalence of beliefs in extramission. In case you think it’s just the preserve of the superstitious or uninformed, there are also claims that large numbers of college educated students continue to profess extramission beliefs despite having had courses covering vision and the visual system [2]. There seems to be a tendency to default to an extramission account, and it can exist alongside a more informed view without the contradiction being obvious.

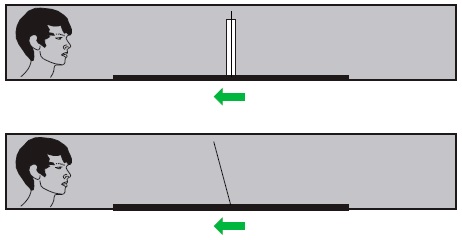

Over the past few years, there has been some experimental work trying to understand this implicit model [3]. In particular, experimenters asked online participants to estimate how far a representation of a paper tube could be tilted before it would fall over completely. Participants would also see a photo of a young man, that could be presented on either side of the tube facing toward it with its eyes alternitvely open or closed.

They found that people (N=147) estimated that the tube could be tipped to a greater angle before toppling over when it was leaning in the direction of a face with open eyes. Similarly, people estimated a smaller angle on average was possible before the tipping point was reached when the tilt was away from the face. The effect disappeared when the image was blindfolded, or when participants were told the face was looking past the tube at the far wall, or that the tube was made of concrete. When asked, only a small percentage avowed explicit beliefs in extramission (it’s not clear why this study found fewer explicit believers in extramission than earlier studies), but the implicit effect remained even when those participants were removed. This is consistent with the inference of a force emanating from the photo that was either supporting or pushing on the tube that depended on the eyes being open. Based on the results, the experimenters estimated the force implicitly associated with the eyes as equivalent to 0.01N, or a ‘barely detectable breeze’. In another recent study, the same experimenters found evidence that the ‘force’ of attention in this implicit model is also in motion, as shown by the fact that attention can apparently induce motion adaptation perceptual effects, where the presentation of one stimulus effects the response to a second stimulus [4]. The waterfall illusion is an example of motion adaptation, where if you stare at cascading water for about a minute and then look at stationary rocks, the latter can appear to be moving upward. The authors found that the presentation of a static image of a head looking in one direction affected people’s subsequent judgement of motion direction in a moving field of dots. Again, note that the motion is implied, the first image showed no motion. In the words of the experimenters:

The emerging picture is that people construct a descriptive model of the attention of others, that model is constructed implicitly and automatically, sometimes at odds with people’s explicit intellectual beliefs, and the model contains some physically incorrect and schematic features. In our interpretation of the data, in the model, other agents are represented as a source of an energy-like essence that attends to information about the world; the essence radiates invisibly through space where the agent directs it; and the essence touches and even physically affects the object of attention. As bizarre as this implicit perception may seem to modern intellectual sensibilities, we suggest that it may represent a computationally easy way for the brain to keep track of sources and targets of attention in a complex social world.

.…

We do not look at another person and intuitively understand, “The neurons in her visual system are engaged in a signal competition via lateral inhibitory interactions, resulting, across hierarchical layers, in one particular visual signal being enhanced at the expense of others, allowing the winning signal to dominate cognitive networks.” Instead, to model another agent’s attention, it is necessary to construct a simpler, more schematic model, one that can be computed on the basis of minimal cues and without impossibly large computational resources. Our data suggest that attention is modelled at least partly like an invisible fluid that flows from the agent to the object of attention.

From [4]

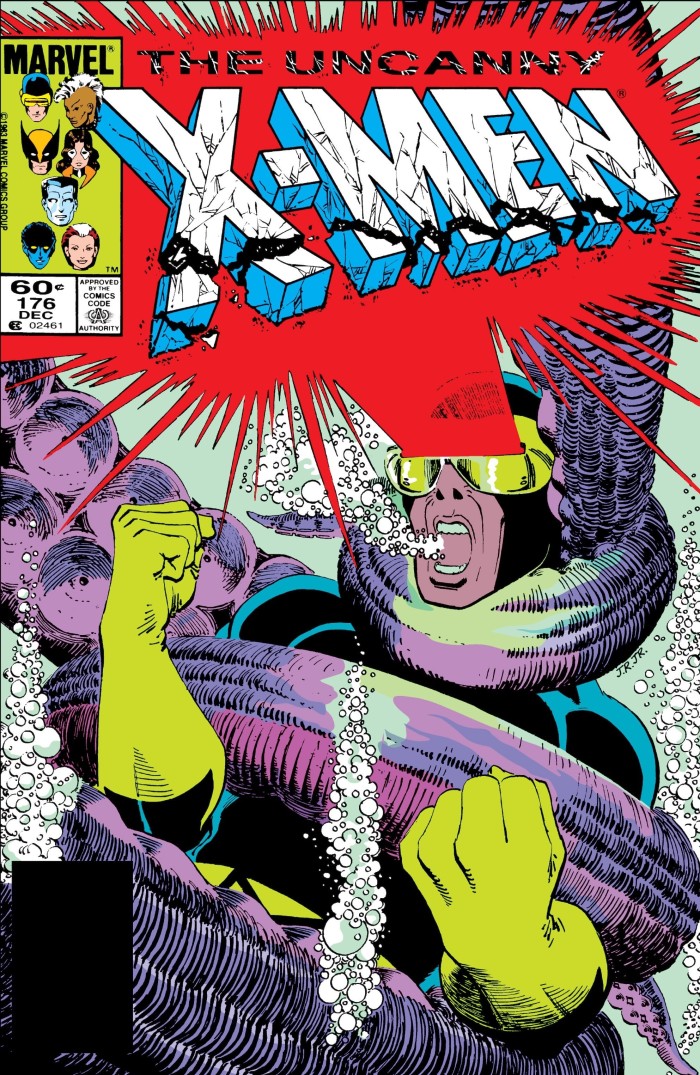

Now, while literary allusions and visual illusions are all very well, I have to admit my immediate association with a moving beam of force emanating from the eyes is nothing so highbrow. Rather, it makes me think about the world of superheroes where eyebeams of energy are something of a trope. This may be another reflection of our default ideas of powers associated with the eyes. Mostly, though, superpowered eyes shoot lasers or particle beams or heat and x-ray beams. I put it to you that the kudos for the creating the purest totem of our apparent collective perceptual unconscious goes to Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, for Scott ‘Slim’ Summers a.k.a Cyclops. The long suffering leader of the X-Men has eyebeams of an unusual flavour in the form of ‘optic blasts of concussive force’. Indeed, they are continuously and involuntarily emanating from his eyes, and when a particularly strong blast is called for he’s depicted as bracing himself which to my mind underscores the idea that he’s imparting a ‘push’. I submit the following cover art from Uncanny X-men 176 as depicting all these points and – more importantly – for just being comics as hell, tentacles and all.

References

[1] Gross, Charles. (1999) The Fire That comes from the Eye. Neuroscientist 5: 58-64.

[2] Winer GA, Cottrell JE, Gregg V, Fournier JS, Bica LA (2002) Fundamentally misunderstanding visual perception. Adults’ belief in visual emissions. Am Psychol 57:

417–424.

[3] Guterstam, A., Kean, H.H., Webb, T.W., Kean, F.S., Graziano, M.S.A., 2019. Implicit

model of other people’s visual attention as an invisible, force-carrying beam

projecting from the eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116,

328–333.

[4] Guterstam A, Graziano MSA, Implied motion as a possible mechanism for encoding other people’s attention, Progress in Neurobiology (2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101797

4 thoughts on “Your Brain Through…History: the eyes have it”